On Impact & Innovation with Architect Anne Fougeron

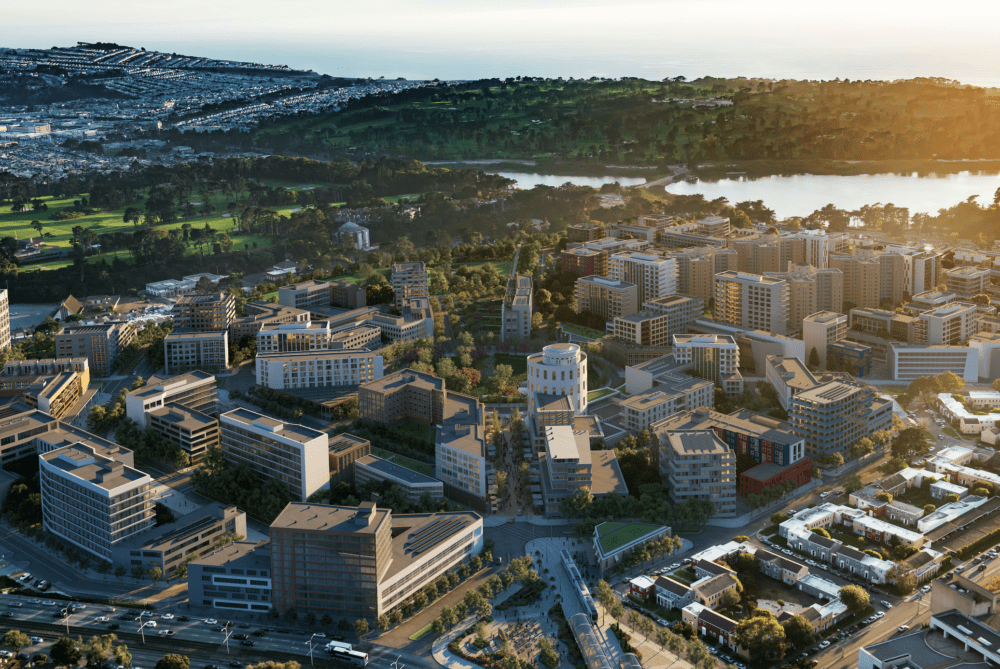

When Maximus set out to transform Parkmerced into the largest multi-family development in North America, it did so with the intention of reimagining the way residents live, connect and experience an urban environment. In order to create a welcoming, inspiring space, Maximus invited top-tier architects to map the future of Parkmerced’s 152-acre community.

Anne Fougeron is a renowned architect with a long history of crafting innovative residential and commercial buildings in the San Francisco Bay Area. Fougeron brought her decades of expertise to Parkmerced, where she was joined by a stellar team of design experts asked to reimagine how residents can better engage with both private and public spaces. We spoke with Anne about her team’s approach to design and how architecture can strengthen communities, improve well-being and respond to the evolving needs of residents around the world.

Where do you and your team find inspiration when embarking on a new project?

A big source of inspiration comes from fully grasping the project’s sense of place. For example, we’ve been working in San Francisco for a long time and now know it intimately — which enables us to improve upon the fabric of the city.

For this reason, we firstly consider the building’s unique location, geography and topography. Our design approach will differ quite significantly when working on a project in San Francisco compared to one located in Big Sur. While much of our inspiration is project-specific, we are consistently moved by natural California light and air, as well as the beauty of the Bay Area.

You’ve had a hand in designing a variety of multifamily developments. What makes the Parkmerced design stand out to you?

The idea of invigorating this massive development, which carries so much history and is so different from anything else that you’ve ever seen, is incredibly interesting. You’re not remodeling a house — you’re remodeling a gigantic, urban project.

This opportunity was interesting to us because it’s important to look at projects existing within our town or our state and think about how we can better modernize and reuse them. It’s a really green way of thinking about design.

For your Parkmerced design, did you build upon an existing structure?

We utilized concrete 12- or 14-story towers that were previously built, while reimagining uninteresting buildings that did not align with our vision. We took a site that was very low density and designed around the remaining towers to not only increase the density, but also make for better urban design.

It’s interesting to work with such a wide variety of different architects, with all of them working on different sites and cross-pollinating based on what they’re interested in. It’s an incredibly exciting project and it will evolve dramatically in the next 10 years.

The intersection of design and innovation is a large part of your work. How will we see that marriage manifest in the Parkmerced development?

By working with the developer, we used the slope of the site as a way to stack the building in different ways to enhance views, achieve an exciting building aesthetic and increase the number of units, including the addition of studios and one bedrooms. The building also features a large courtyard that’s shared by the community. Residents can cut through it to get to the other side or to reach the towers.

We appreciate a building that encourages community interaction within the neighborhood, instead of just serving as a gated community.

Your work is also deeply influenced by natural light. Can you explain how this element will play a role in the design?

Light and windows played a big part in how we thought about this building’s design. We wanted to incorporate as many windows as possible and we always try to work with units so that residents receive light from more than one direction.

We wanted to avoid a double-loaded corridor building and instead organized an open walkway. This design works better for the site and offers a more pleasant living experience as residents will walk outside to get to their unit and, upon entering the front door, be greeted by huge expansive windows.

In your experience, how does architecture impact quality of life on an emotional, mental and physical level?

I think for us, it’s always about trying to find the balance between how people interact with the building, what amenities we can provide them and how much light we can bring to the space. A pleasant living environment plays an essential role in well-being — and we may not even realize it until our environment changes.

So for us, it’s about believing that, fundamentally, designing architecture and shelter is an incredibly important endeavor. We try to make each space and place as nice as possible, where people have the opportunity to really interact, feel good and enjoy the building that they live in.

How do you see architecture changing in terms of what’s happening with the pandemic?

This is a really interesting question. I think that we’re going to have to look at what it means for people to be working at home and what kind of environments we can provide to comfortably do so.

We’ll see if that will make a change in the way we think about designing units. Previously, there was a lot of emphasis placed on communal spaces. Units were getting smaller while communal spaces in buildings were becoming bigger. Yet now, when all the communal spaces are empty because you can’t use them, it makes you question if you should have given units another 25 to 50 square feet for more desk space.

As this was your first time working with Maximus, what stands out most to you about their approach to design and residential developments?

A young developer striving to do innovative work, Maximus was willing to hire a more innovative team of designers. While some development teams are more established and continue to operate the way they’ve been operating for the past 50 years, Maximus was different. They were more like, ‘Okay, what’s the best solution for this building and this place and how are you going to do it, and what do we do, and how do we make it work?’ We enjoyed learning how to do this, together.

Ultimately, how do you gauge the success of a development?

I think, in general, it comes down to how the development fits in with and enhances the neighborhood. Also, I think success comes with innovation. I always say that whatever project you’re doing in this city, it’s sort of like a remodel — you’re basically adding one last piece to an existing puzzle. If you try to place a puzzle piece into a space that doesn’t fit, it’s not going to go very well. We want to help enhance what already exists and also think about the future of that environment. The development has to complement what came before it, while also achieving something better.

What is your dream out-of-the-box project that you would love to work on?

One of the things that I’d love to work on is from our City of the Future project, where towers were placed next to each other out in the Bay. It’d be interesting to see how we could make that work — a hybrid type of building typology, a place where you can work and then pick up some vegetables across your hallway. You could take a boat to get to your house. You could have BART coming in and dropping you off. I’d love to work on something like that — something that unravels different concepts that everybody’s been thinking about and puts together the different pieces into an integrated project.

share story